We’ve all heard it before. The saying “they’re a just a one man team” has been used to describe various teams over the years. Whether it’s been Kevin De Bruyne’s Manchester City, Robert Lewandowski’s Bayern Munich, or Cristiano Ronaldo’s… well, every team Ronaldo’s played in; at times it feels like the complex tactics of thoughtful managers could just be boiled down to “give it to him, he’ll get us a goal”. When that player is missing from the team, things tend to go wrong, and that reliability on a single player can cause trouble at times. But what exactly makes a team a “one man team?” Does that one man have to be a striker, or can it even be a defender? When looking at the data produced from several matches over a season, it is possible to take a good look at whether some players are carrying their team’s output on their backs.

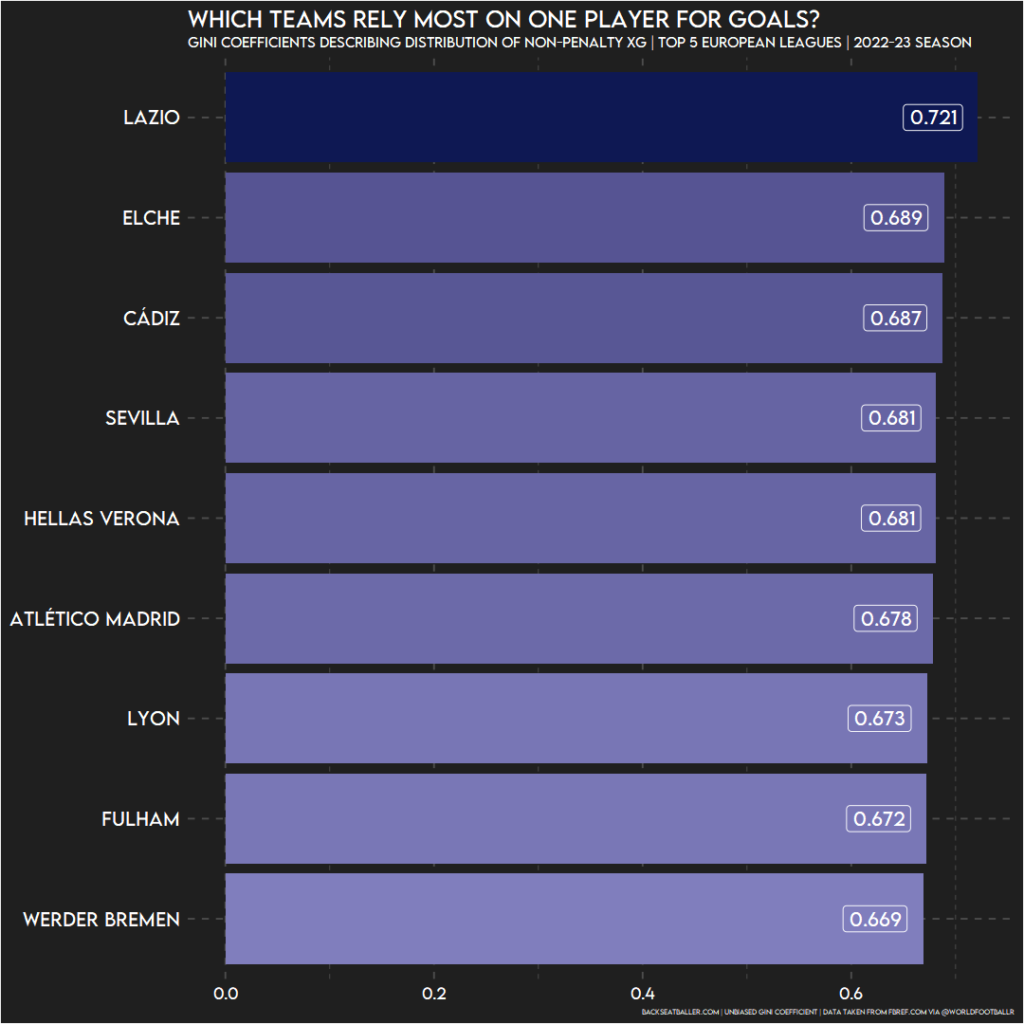

One obvious area when thinking about over-reliance is goals. When one player is responsible for the majority of a team’s goals, their importance cannot be understated. To help get an idea of how goals are distributed across a team, we can look at Gini coefficients. In economics, Gini coefficients are often used to measure the distribution of income within an economy to make judgements on wealth inequality. With a coefficient of 0 meaning total equality and 1 meaning total inequality, using a Gini coefficient can be a very good way of seeing whether the share of goals is equal or unequal across a squad.

If we look the distribution of expected goals for teams in Europe’s top five leagues, then we see that Elche, Cadiz and Lazio have the highest Gini coefficients – that is, they rely the most on a single player compared to other teams in Europe. Looking at Lazio in particular, they have the highest coefficient of all teams (0.721).

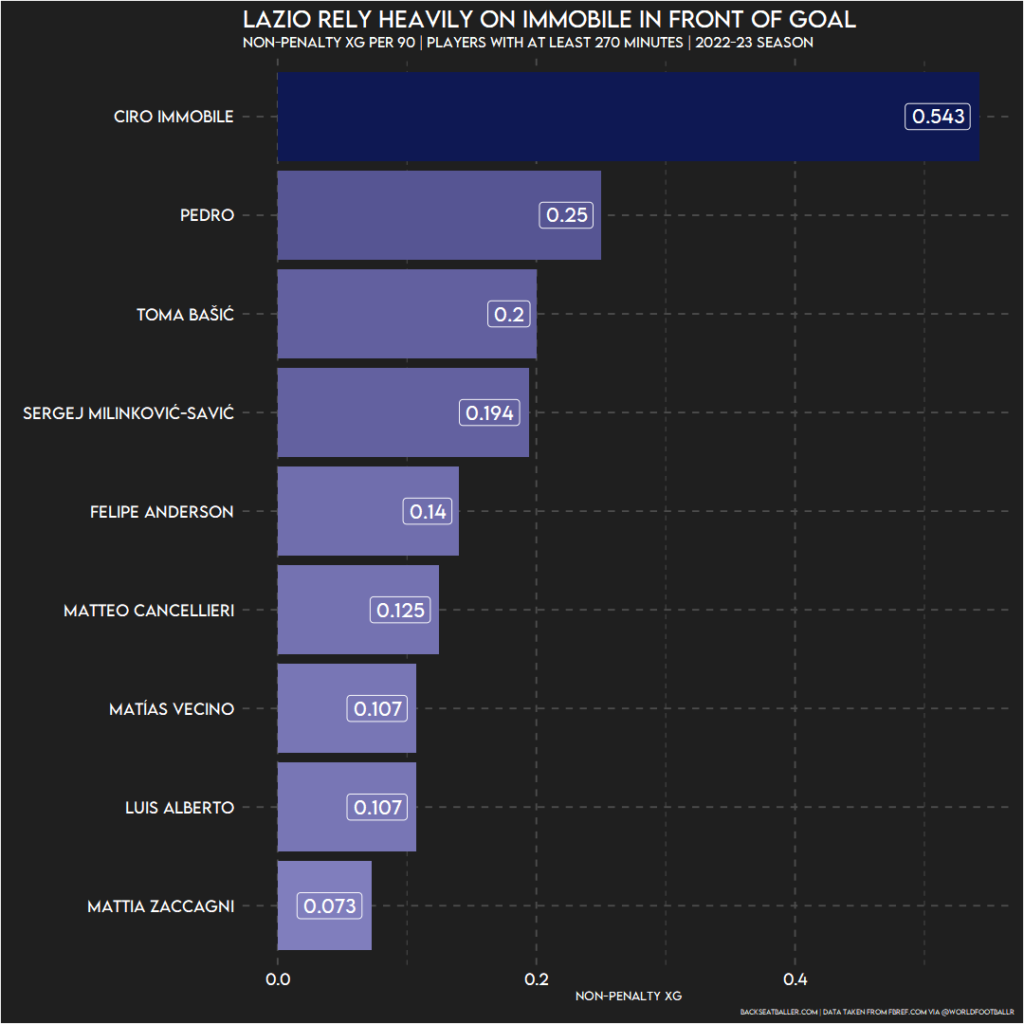

It’s no surprise that Lazio heavily rely on Ciro Immobile for their xG output. The ever-prolific striker has scored 5 goals so far from 4.5xG as the Italian looks to add to his Golden Boot collection and has always looked to be Lazio’s focal point when going forward.

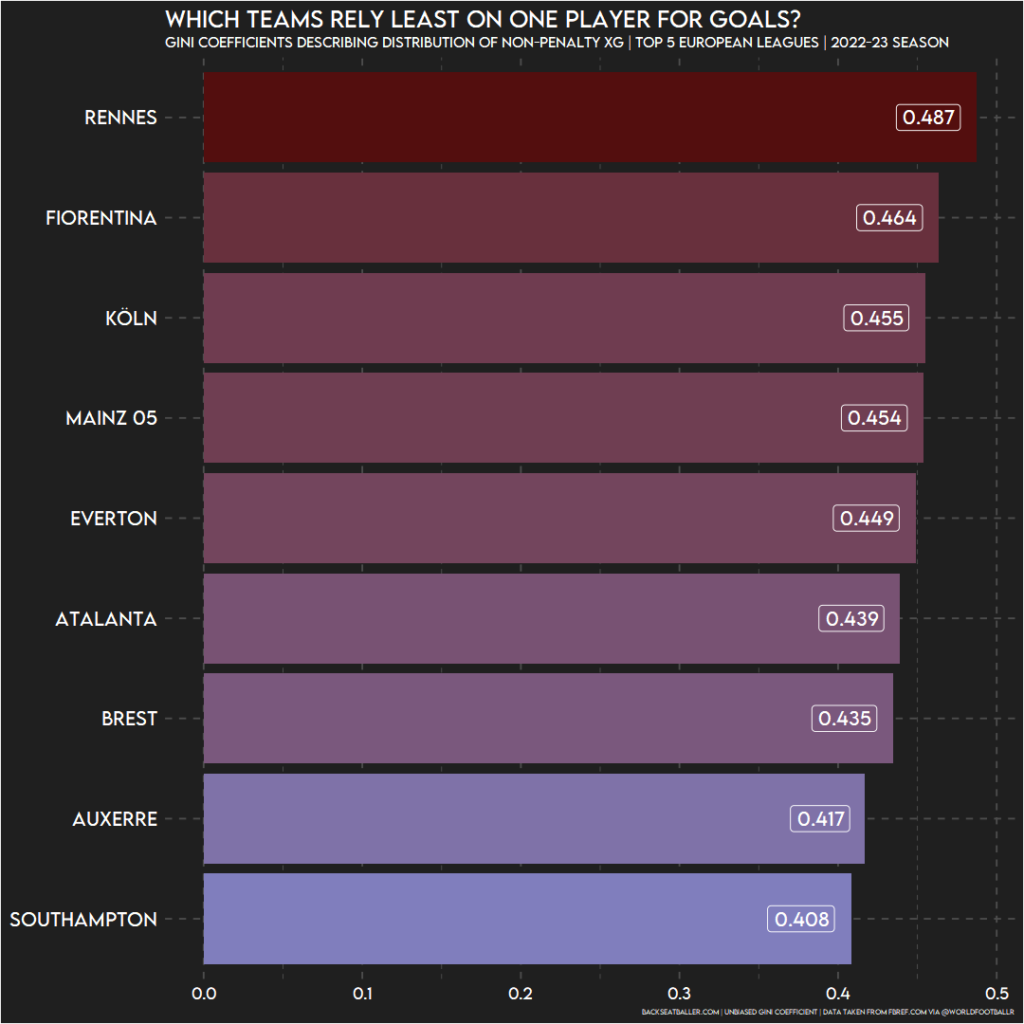

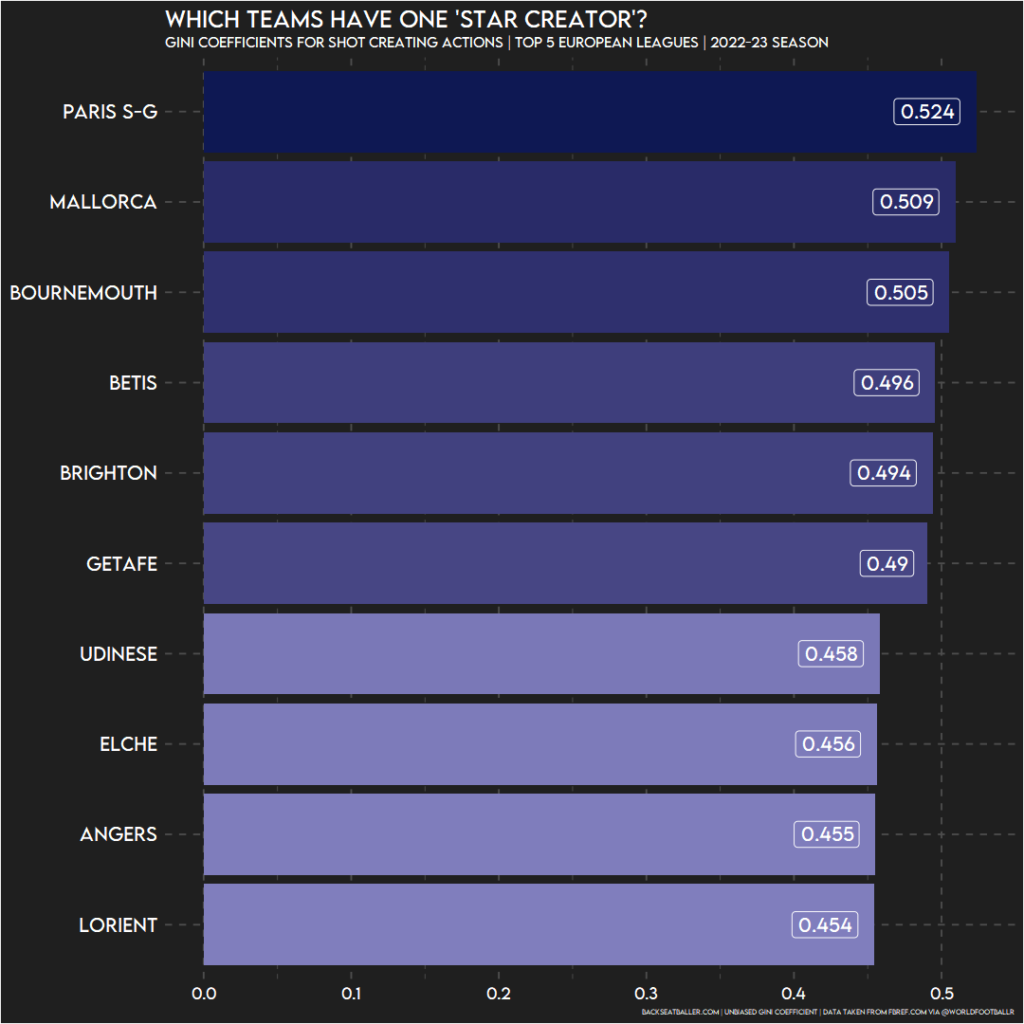

On the other end of the scale, Rennes have the most equal distribution of expected goals across their squad – the 0.293 xG gap between Ciro Immobile and Pedro covers the top five players for xG at Rennes. However, this doesn’t necessarily make Lazio more of a one man team than Rennes. However, having an unbalanced xG distribution doesn’t define a one man team. One player may be responsible for creating lots of chances for several players at Rennes, but several players could be creating chances for Immobile. Arguably, removing Immobile at Lazio would have less of an effect on the team compared to if this hypothetical star creator was taken away from Rennes. Calculating a Gini coefficient for the distribution of shot creating actions will help to locate any star creators across Europe.

Elche make another appearance amongst the most unequal clubs in Europe. Maybe they aren’t a one man team – they aren’t relying on the same player for both creation and goal scoring, making them a two man team at worst? In general, players don’t do all the creating and all the scoring themselves, unless they are only attempting to score solo goals by dribbling through opposition defences. Even one man teams don’t just rely on one player for everything.

The team with the most inequal SCA distribution is Paris Saint-Germain. PSG could be described as something of a “three man team”, relying on their front line of Messi, Neymar and Mbappe for goals- the numbers back this up. In terms of goalscoring, PSG are within the second and third quartile for inequality (they rank within the top 50% but below the top 25% for reliance on one player); Kylian Mbappe ranks top for npxG (0.88 per 90) with Messi and Neymar not too far behind (0.60 and 0.59 respectively). For chance creation, as shown above, Messi and Neymar do most of the creating, but Mbappe does a little bit too. Within that front three, the roles are clear: Messi and Neymar create chances for Mbappe to shoot, and they do that very well. Mbappe has recently been criticised for adopting a “selfish” playstyle, but when the system is built with him as the final part of attacks, and when he is involved in many of those attacks every game, is it fair to refer to him as selfish, or is it just Christophe Galtier’s system working as intended? Looking at Gini coefficients can help to answer questions like this.

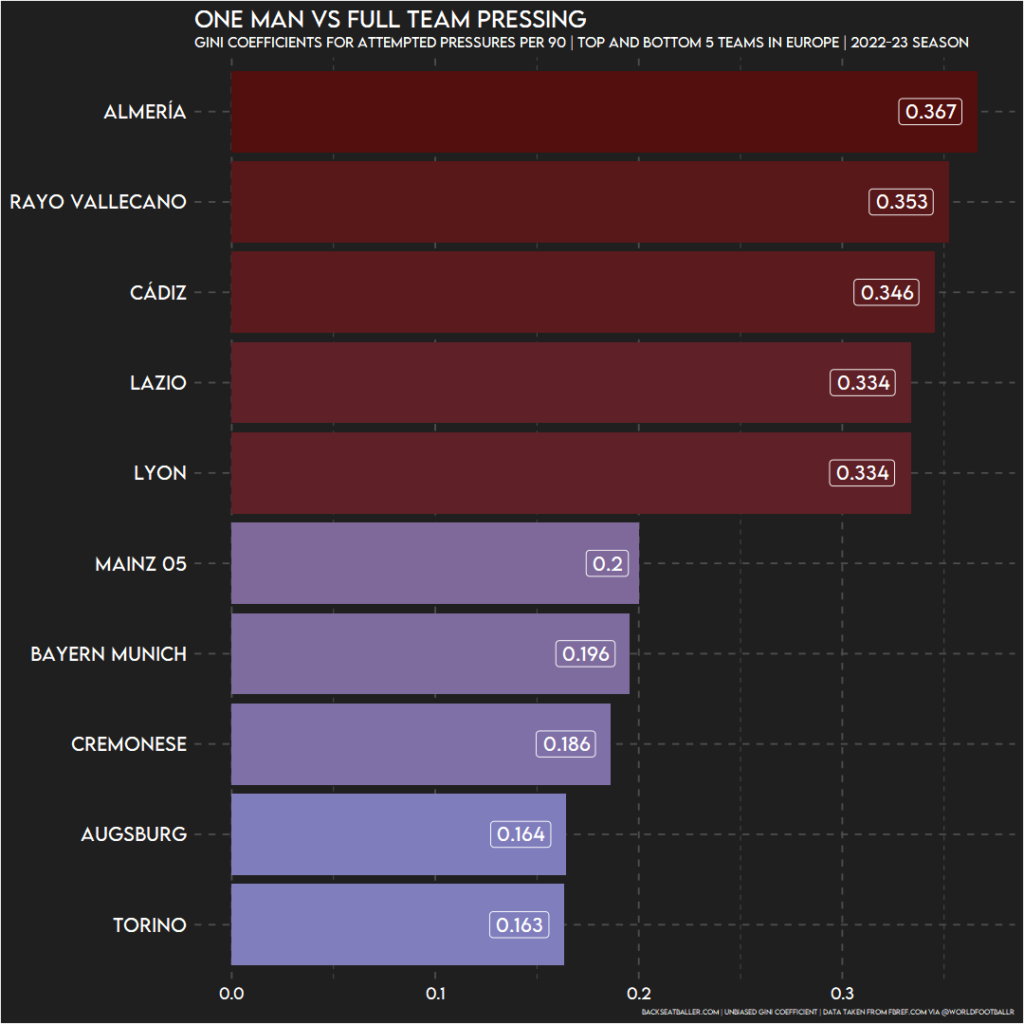

This method of answering questions can also be used on the defensive side. How reliant are teams on one man in the press? For clubs like Almeria and Rayo Vallecano, fewer players are left responsible for pressing compared to teams like Torino, Augsburg and Bayern Munich, whose players share the burden. When a team rely heavily on one or a small group of players for a press, it become easier for an opponent to bypass once those players are identified. Long balls may be played from defence to avoid being caught out by pressing forwards, or patient play from technical players may force opposition midfielders to be pulled out of position, leaving space in behind. When looking at attack, Gini coefficients may be useful in determining whether man-marking specific players could be a viable strategy. For example, a team that plays against Lazio may focus on marking Ciro Immobile out of the game, forcing Lazio to change up their playstyle somewhat. Stopping a world-class level striker from getting into scoring positions is a lot easier said than done, however.

So how can we identify a “one-man team”?

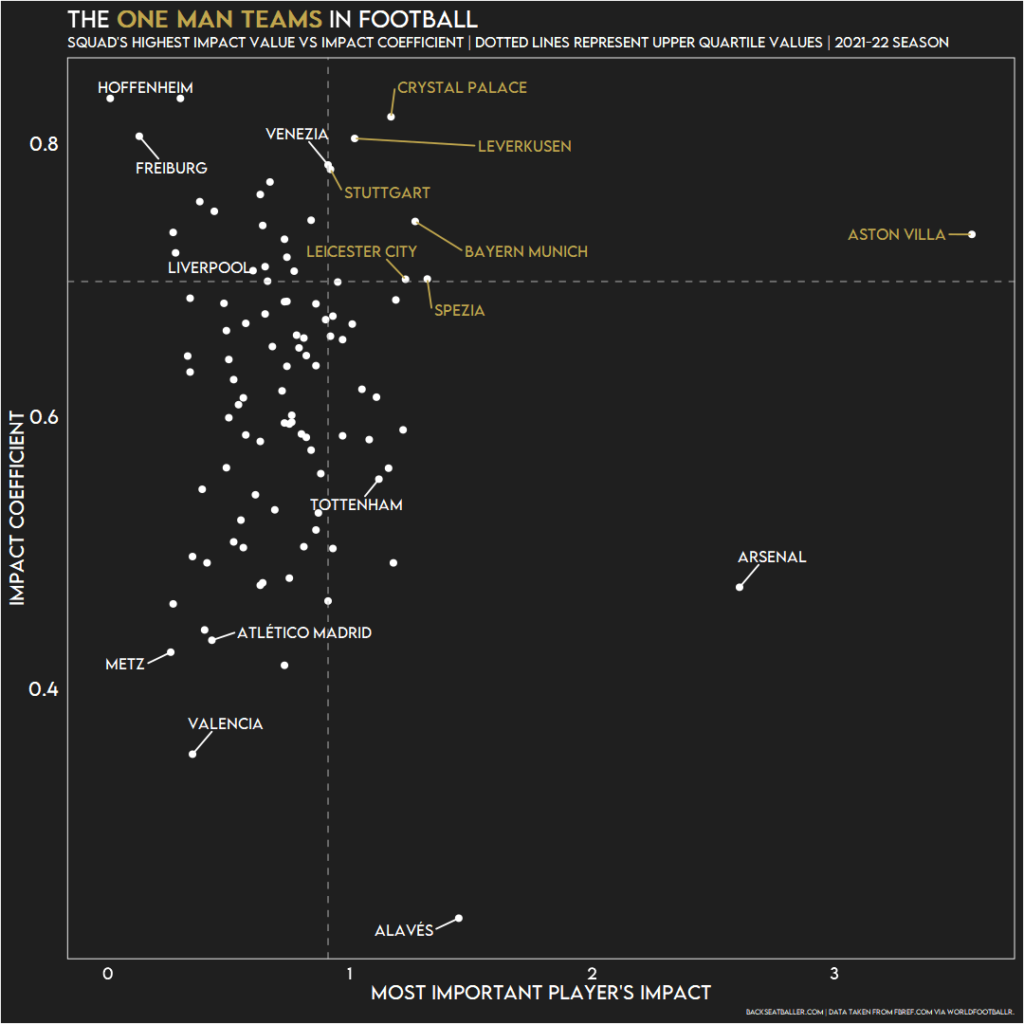

Whilst looking at coefficients in specific areas can be useful to get an idea of a team’s tactics, ultimately, the main thing that shows how much a team relies on a player is how they perform when that player isn’t on the pitch. When a team’s most important player isn’t playing, the rest of team’s performance is noticeably worse. One final Gini coefficient, looking at the change in expected goal difference (xG created minus xG conceded) when a player is on the pitch versus when they are off it, will help us create a definitive list of one man teams.

Formulating this final plot took a couple of steps. Firstly, some teams played better when certain players were taken off, leading to negative values for xGD (change in expected goal difference) that needed to be accounted for, as Gini coefficients don’t deal with negative numbers very well (In economics, negative income isn’t regularly seen). To do this, instead of looking at the absolute impact a missing player makes, this Gini coefficient only looked at the negative impact being made – players with a negative value (taking them off has a positive effect) overall would have 0 negative impact. This final calculation created an “Impact Coefficient”, a Gini coefficient describing the distribution of negative impacts that come with taking certain players off. A high Impact Coefficient means that that team has one or two players that cause a disproportionately high drop off in expected goal difference when they aren’t playing.

The Impact Coefficient won’t tell us the whole story, however. Two players from two different teams may have a much larger impact than the rest of their squads, but one may have an impact of 0.3xGD whilst the other may have an impact of 0.6xGD. Clearly, one player is more important to their team than the other, but the Impact Coefficient doesn’t account for this. So, to find our one-man teams, we need to find those squads that have one player with an especially high impact value compared not only to the rest of the team but compared to all other players in Europe.

By plotting each team’s highest impact value against the squad’s Impact Coefficient, we can finally single out our one man teams. Last season, these seven teams were Aston Villa, Leicester City and Crystal Palace from the Premier League; Bayern Munich, Leverkusen and Stuttgart from the Bundesliga; and Spezia from Serie A. Venezia were very close to being a part of that group, but Mattia Aramu’s 0.91xGD fell just outside the top 25% of each team’s highest impact value. Arsenal and Spurs fell into the category of teams with a group of players that have large impacts, having a very valuable core (for example, Aaron Ramsdale, Gabriel, and Ben White had the three largest impact values at Arsenal, with Gabriel having the second highest overall). Liverpool, Manchester City and Freiburg were amongst clubs that could mostly interchange players without much issue bar one or two that caused slight problems (like Joel Matip at 0.63xGD and Gundogan at 0.60xGD). Manchester United, Atletico Madrid and Dortmund were able to add or remove players without any substitution having a large impact on performances – more of a symptom of overall underperformance across the squad, especially in the case of United.

Those seven one man teams all had one player that caused a large drop in quality in the team when not playing. By far, the most important player was Matty Cash of Aston Villa, with an impact value of 3.57xGD. Cash only missed 40 minutes of Premier League football last season, but in those 40 minutes Villa conceded 4 goals, with three of those coming in the last 10 minutes away against Wolves in a famous 3-2 defeat. Villa’s defensive structure wasn’t as rigid with Ashley Young in at right back instead of Cash, and the team lost the Pole’s attacking output as well. Mark Guehi (Palace, 1.17xGD), Waldemar Anton (Stuttgart, 0.92xGD) and Dimitris Nikolaou (Spezia, 1.32xGD) were examples of centre backs that steadied the ship defensively, whilst Moussa Diaby (Leverkusen, 1.02xGD) was valuable in attack. Interestingly, the main man at Bayern Munich wasn’t Robert Lewandowski or Thomas Muller, but Leroy Sane (1.27xGD). High percentile rankings across Europe for shot creating actions as well as successful pressures highlight the German’s importance in both aspects of the game.

Gini coefficients are not just useful tactically when picking out certain key players to mark out of a game, but also in recruitment. Take the case of Leicester City, whose main man was Youri Tielemans (1.23xGD). Tielemans’ contract is set to expire at the end of this season, with the Belgian unlikely to extend at the time of writing. When he does leave, the Foxes will be left with a gaping hole in midfield that will need to be filled by a player with the same level of positive creative impact. Leicester notoriously only signed one outfield player in the summer transfer window, and that was a centre back, not a creative midfielder. Knowing about Impact Coefficients would allow a team to sign suitable backups to make sure that creativity and defensive shape isn’t thrown off as much when a key player is sold, injured, or just taken off near the end of the game. Overreliance on a small number of important players is a risky game and in modern football, with its fixture congestion and high activity transfer windows, being a “one man team” may be a glaring warning sign for a team’s long term sustainability on the pitch.